‘Have you read Gobodo-Madikizela’s book on Eugene de Kock yet, Jude?’ my long-suffering husband asks. He’d read it on the plane to Cape Town. ‘You’ll find it interesting.’

‘Mmm,’ I mumble, trying to think of another excuse, another reason, not to hold “Prime Evil” in my hands. ‘I’ll get to it later.’

But still I resist picking it up and reading the first page.

I’ve had enough of that sort of thing, I say to myself. I sat, night after night, listening, watching and finally weeping for their pain and my guilt at the stories blurted out in the television visuals of the Truth and Reconciliation committee in those early days of our proud New South Africa. I just want to move forward into the future, to honour the innocent dead by making my contribution to a society which offers “a better life for all”. To be just an ordinary citizen in a nation where everyone has an equal national pride that is as race-less and colour-less as it is passionate.

Until one day, a cold miserable day, when I’m warm and safe in my ironically white-and-black suburban house, and the wind howls and yelps outside. On that day I force myself to open the book and face what I have feared all along: the judgement of a fellow human being.

A fellow South African. One who knows. One who lived through the same days and nights as I did, but in a way I had never perceived as possible.

And so we finally meet – we three. A man, committing murder in my name. A woman, suffering under that cardinal sin. And myself, blind no longer and, with nowhere left to hide, more afraid than I have ever been, for who is to be judged and who the judge?

As I devour the short journey of less than two hundred pages; drawn hurriedly from paragraph to paragraph in a combination of righteous shame and not-so-righteous indignation, I’m left as exhausted and sweaty as if I’d taken a journey of a thousand miles.

Perhaps I had. For there – behind the white man beyond moral hope and the final praise-singing for a black woman who is moral hope – lay the best and the worst of me.

Now, here I am. Writing to you, dear Pumla, in an attempt at the dialogue you state is so essential in helping this fledgling democracy of ours honourably fulfil the great potential she has shown so far and in which today, nearly twenty years after freedom came, we struggle with corruption, violence, lack of education, unemployment and other governmental failings, somehow worse than those of the apartheid government because *this* government all the people of our beloved country believed in and trusted.

I do not know whether I write to you with a plea for redemption or as an act of justification. All I know is that my belief in this brave new world of ours is wavering. For, after reading your book, my heart and my head - my shame and my pride - are in conflict as never before.

On my travels through the pages of your remembrance, there are times when I weep for the insanity of a little boy who witnessed his father’s gruesome and unnecessary death. Where is that little boy today, I wonder, now that he’s grown to be a man?

There are times I fling your precious testament from me in anger as, despite your sincere attempt to remain non-judgemental, you subtly sneer at the apathy of collective white South Africa, that tribe of mediocre souls – of which I am indubitably one – whom, you feel, didn’t suffer as you did. While others cried and died in agony, I gaily lived my life, reaping the rewards of a social system I was too comfortable in to challenge, and too blindly obedient to question.

Then I gasp in awe at your courage; at the pride and strength you showed in rising above the humiliations of your own oppressed past. Still I snigger knowingly – and with some relief at this evidence of your own humanity which makes you appear less saintly – when I realise that your ability to transcend hate is not quite as evolved as you believe, for you are clearly unable to forgive Mr F W de Klerk, the last President of apartheid South Africa and another of our Nobel Peace Prize winners. The man who irrevocably opened the prison doors and who, although you might not like to acknowledge it, set us all free.

In your compassion and empathy for de Kock as a fellow human being, you seem to place such credence on the words of a man who chose to embrace his evil. How will you respond to my words, I wonder? Will you say: what has she, in her trivial, privileged life, suffered? What remorse has she shown?

Or will your compassion and intellect allow you to clearly see into the mind and soul of an ordinary white South African, a single self with no claim to fame or infamy other than that I did nothing?

Let me state it plainly, so that it’s out in the open, not taunting me from the shadows in my heart.

Unlike you - with your impressive and somewhat intimidating personal biography: your academic qualifications and international connections, your participation in the TRC, and the moral probity your black skin automatically bestows on the words you write like a badge of suffering - I am Nobody. There! In all humility, it is said bluntly and with no adornment. I am nobody and I did nothing.

And yet, with pride, I say to you, ‘I am also Somebody.’ Like you, a woman of many faces: a wife, a daughter, a sister, an aunt, a neighbour, a friend.

What of those other women? Those other wives, daughters and sisters, also ordinary people and also ‘Somebodies.’ Why did I not cry out in their pain when young white men, young enough to be their sons, pushed hands up their vaginas?

With every cell in my being cringing at the vicious, violent imagery of acts committed in my name, I want to ask you where are your stories of all the ordinary, white people, people like my parents, who did invisible good deeds, not because they were politically inclined (and therefore never got their names in newspapers,) but because it was bred in their very souls to always help those in need, irrespective of the colour of the person who was hungry or cold or being terrorized (do you even care that my mother single-handedly took on an AWB bully who was harrassing an old black man - now there would be a good story for you!)

Can your justifiable pain not allow you to see that good people *did* exist during the time of your suffering, even if they were too involved in their personal struggle to rise above the poverty they were born into to take an interest in politics. Can you not see that, just like the new South Africans today, all these good ordinary people wanted was to give their children (lucky me!) a better life than they had had?

At the same time, I want to resort to the age-old whine of ‘I didn’t know!’ Before I can voice that weak, pathetic cry I see, in my mind’s eye, the mocking lift of your eyebrow at those hollow words.

‘You really didn’t know?’ you ask politely, clinging tightly to your badge of honour as a victim. ‘Come, come, Judy! There are none so blind as those who will not see.’ Your unforgiving disbelief is etched deeply on your face as you say, ‘Our pain was all around you, in the townships and in the valleys; in the cities and in the villages. In every “whites-only” sign adorning the restaurants you ate in, the beaches you swam on and the buses you rode, our suffering was there for you to see. If you’d wanted to.’

All I remember is my white Afrikaner Father sitting around our table, eating and laughing with his black mine colleagues who, day after day, came to him with their cares, their fears, their desperate need for someone to help them with the minutia of a life lived far from their tribal homes. That scene was my childhood normality and I never questioned it, or whether it should be more or different to what it was.

So, with perfect hindsight, today I can only confess, ‘You’re right!’

Remorse slithers through me like an unwanted parasite in my belly. I do not know how to explain to you that the first time I knew how terrible things had been for you, truly *was* only as I sat listening to the perceptions and experiences of other ordinary souls like myself.

Only they weren’t like me: they were black and they lived on the other side of my life.

My head sinks lower, the millstone of guilt becoming heavier and heavier with each page of your book I read.

For I don’t even have the excuse of the cold-faced Afrikaner killer you portray so accurately and so empathetically – that I was a crusader for the apartheid values which he believed were good. I was raised in the Church of England. I’m Anglican and the 1984 Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Archbishop Desmond Tutu, of all people, was my religious and spiritual leader!

And still I was blind.

Was it because, like the ordinary soul I am, I was too busy living my own life - draped in joys and fears and sorrows so unlike yours, but so real to me - to notice you were being so cruelly oppressed? Or was it because there is some inherent evil, some unacknowledged darkness existing within me? And how could the person I thought I was possibly be a collaborator to one of the two greatest human rights abuses of the twentieth century?

Why then, my apathy? Why then did I think that, when the time came for the ultimate measure of my humanity to be judged, I would have accomplished sufficient goodness to be considered a worthy human being when I had made no great sacrifices to eliminate the scourge of apartheid?

The fragments with which I shore up the illusionary ruins of my single self as a decent, honourable human being are varied and many.

Will the slivers of my perceptions from those apartheid days be enough to explain the ambivalence with which I finish reading your book and, closing it, think of a killer who, but for my lassitude, you accuse, could have been me?

Will my memories be enough to refute that bond I do not want and yet cannot escape? Will they be enough to save my soul from the sins of apartheid? Perhaps.

By sharing them with you am I saying I’m sorry that, as a somebody, I didn’t do something?

Oh yes.

Hindsight always gives one a perfect view of what should or shouldn’t have happened at that crossroads in one’s life when one has to make that pivotal choice on which one’s eternal destiny is built. Retrospection of what – in those exact same circumstances of my life – I, me or thee would, should, could have done, make it so easy for me to say now that I’m sorry I never did anything.

Of course I’m sorry! If I’d done something – anything, no matter how small - just think how much easier my life would be now, as I sit contemplating your story on forgiveness.

‘World,’ I would say, ‘Look at me! Just like Pumla I am a Heroine of The Struggle. But I,’ — and here I could smirk as virtuously as you do at times in your story — ‘am a white heroine! One of History’s righteous.’

But I didn’t, and I’m not, and instead I sit and grapple daily with the twin demons of shame and failure.

Shame, because I was too weak to fight for what the world, and my awakened conscience, now tells me I should have fought for then. Failure because, in the recognition of the fact that at a specific moment in time when A Big Cause called to me and you tell me I should have answered, instead “I did Nothing”.

And in the process of doing nothing I became somebody – something – I never thought I was.

So am I asking you to learn to forgive me, as you so heartrendingly learnt to forgive de Kock?

When I have finished my discourse then, dear Pumla, by virtue of the misery of your black life during the apartheid years, you can - in your just and proper role as moral arbiter of the New South Africa - decide on whether it is your right to forgive, or not to forgive me, for my apathy and my blindness, and for my pedestrian inability to rise above the comfort and convenience of my white life during the apartheid years.

Will I then be free of this weight on my soul?

Will I, redeemed and renewed by your gracious compassion, be able to sit comfortably around the log fire in my cosy lounge as I listen, watch and proudly participate in the creation of the myths and symbols of this New South Africa?

Soothed and saved by your forgiveness, can I then gratefully allow my single self to, once more, become integrated with that mediocre, undifferentiated mass of ‘good people’ who sleep soundly at night, knowing that the future of their humanity rests safely in the hands of the wise and noble leaders they have voted into power?

If only forgiveness were that simple.

19 comments:

This was so powerful I can not think of anything to say. Thank you for sharing.

I'm overwhelmed with emotion and gratitude for what you wrote here. You stirred me to the core. Thank you Judy. This is writing of substance. Powerful in every way.

ANNE: Thanks! First time I've ever stripped my real thoughts so bare in my writing. Was a bit long for a book review though!

KELLY: This was a powerful (but very one-sided) book to read and, as you gathered, stirred powerful emotions in me. Thanks for your comments!

Thank you for sharing. So deep.

I have a lot to think about since anything remotely attached to politics sends me in the opposite direction.

SHAZ: You've just pinned down what bothered me about this book - despite the sad (horrible!)truths between its pages, it was so "politically correct." And, like you, politics and me don't mix!

If we stripped away the politics in this country, we'd be left with the true heart of South Africa: people of all colours and shapes and temperaments, people who just want to do the best they can on life's long journey and move forward into a peaceful, stable and prosperous future for all of us.

What a gift you have with words.

I think the blindness you speak of has happened before and will happen again. How many Germans really understood what Hitler was doing? How many white Americans really understood what was happening to the Native Americans or the blacks in the South? How many people understand the millions who died under Mao Tse-tung? The list is long. And if they had really understood, how many would have actually done something, or been capable of doing something?

I think when you are born and/or raised into those kinds of systems there is a subtle kind of brain-washing that goes on. And the longer the system is in place, the deeper that brainwashing goes. That doesn't excuse anything, but it helps to explain how people go about their lives, dealing with their own pain and troubles, wearing a strange set of blinders they are not even aware they are wearing.

When the blinders are stripped away they either do as you are doing, struggle with how they could have been so blind, or they put on a new set of blinders which prevents them from looking too deeply into themselves and which permits them to go on living as though nothing ever happened.

Your struggle is your own and a valiant one. Someday, on the other side, there will be peace.

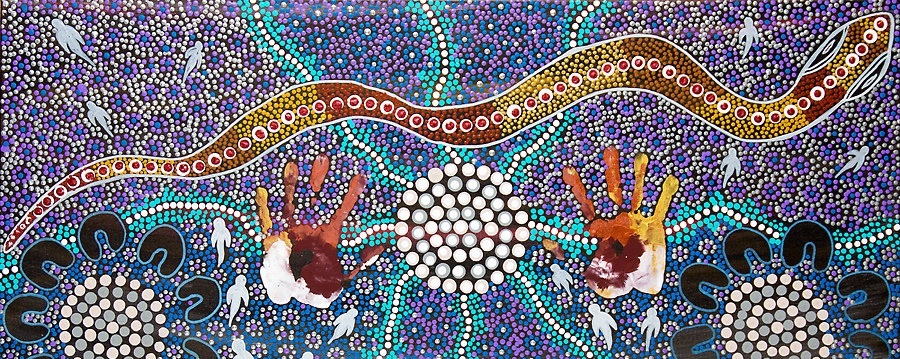

BISH: Yes the list goes on and on...the aborigines in Australia, the Maoris in New Zealand, anywhere there was colonisation the western world has a poor record.

Talking about blindness - that's why the hymn AMAZING GRACE always makes me howl. No matter how many times I hear it, when that last line of the first verse is sung, the tears begin, perhaps because I really have felt that awakening from blindness to grace...

Amazing grace! How sweet the sound

That saved a wretch like me!

I once was lost, but now am found;

Was blind, but now I see.

September 20, 2012 4:22 PM

Powerful post. Thanks for sharing, Judy. Your choice of heart felt words is touching.

Ann

ANN: Thanks! I wasn't sure whether I should post it, because I thought it was a little too honest. I suppose it shows that one should write from the heart and leave nothing out to make writing really work.

Judy, I had emailed myself this post, knowing that I wanted to read it when I had plenty of time and emotional strength to permit me to sink into it fully. I finally read it and, as others have commented, I am left speechless by its power and raw honesty. We are honored by your willingness to open your heart to us. I don’t know if I can assert that South Africa’s particular cauldron of issues is more complex than most. After all, life is in its essence complex. Just its very mystery introduces complexity. Yet, your nation seems to be a crucible, in the present era, for the challenges humanity faces in defining what is good and what is evil. I hope you submit this far and wide, for it deserves to be read. Indeed, I will post a link to it today on my blog.

Here is the link to my post:

http://judithmercadoauthor.blogspot.com/2012/09/a-human-being-died-that-night.html

This ost must have been hard to write. And for that I commend you. There are no victims or victimisers in wars, or civil uprisings. Or rather, there are only victims. The real guilty usually escape in their private jet when the going gets tough. The executioner is caught red-handed holding his axe upon the prisoners neck. But the person who gave the order is nowhere to be found.

You've written such a powerful post that words fail me to describe it. Many thanks.

By the way, I will be using A Lamp at Midday for a future post on literature. I'll keep you posted. Many thanks. I loved the book.

Greetings from London.

Hi Judy .. I came via Judith's post - I would have got here to read this incredibly powerful post. You certainly have a way with words - and an ability to look at life in a different way ... South Africa is a huge melting pot and deserves for everyone to be happy.

I just hope SA can stay the course in the present situation.

However back to your post - I can see the political put off ... I'm not politically oriented ... but having lived in SA I can understand Pumla's writing and your posting ... especially as I had friends involved in the fight to end apartheid and others on the edge - yet coming from the UK, with little or no understanding at that time - just me being me automatically sided with the need for freedom for all.

My learning grows being around the blogosphere ... you've inspired me to get the book and then I can pass it on to other SA friends ... with your post ...

Thinking of you - the post title made me think of other things ...

Hope you can have a peaceful weekend - this books stirs deep emotions - and your husband was right ... cheers Hilary

CUBAN: While I agree that in wars, civil uprisings, all peoples - whichever "side" they're on suffer consequences, I'm nervous of the term "victims." I prefer "wounded" - where "victims" imply a passive state of mind, which has the potential to foster an inability to accept responsibility for one's choices, being wounded by societies structures, implies that one has the capacity to heal and move forward. Thanks for your kindness, and I hope you had a great holiday with your family. :)

HILARY: Thanks for your thoughts - always interesting!

JUDITH: Thanks so much for linking to the post. Much appreciated. :)

I totally agree with you, Judy. Wounded sounds better. The other problem with the word "victim" is that unfortunately many people take advantage of their plight to appropriate their voices and thoughts.

Greetings from London.

Fraud Scam Alert

I have been the subject of an internet scam/fraud attempt, ongoing, which was facilitated by the About Me information I had posted and the Contact Me button on my blog. A friend from university, who has since gone to the dark side, contacted me through that email info and I fell for it. He used to be one of my best friends at university, but as the Alumnae Office told me, there are plenty of my colleagues from my otherwise illustrious alma mater who are now in jail, etc. Indeed, they contacted him and he shrugged off the attempt. I have since removed all About Me details and have removed the Contact Me button. The nightmare, though, continues. It has become a full-time job to head off the identity and financial threat. I am in the process of changing the blog's email of record, but it is on my long list of to-do things in this awful incident.

This is powerful Judy and I read it all the while thinking was it you who wrote it or a beautiful writing you quoted. You write so beautiful, deep and bare.

How are you Judy. I hope you are well.

Lisa (oceangirl)

Hi Lisa Thanks for your complimentary comment - this post is is all my own original writing (it’s actually my response to reading the book called “A human being died that night”), and basically a first draft too. When I forget to think and just write from the heart I write better than when I try to be too clever and think things through! :)

Post a Comment